Intelligent asset management takes time

As the French saying goes, ‘Time takes revenge for what we do in haste’. In today’s world of mouse clicks and instant gratification, we forget all too often that nothing happens overnight, and that the longest-lasting gains are those made over the long term. Even the financial world cannot escape that rule.

Every long-lasting gain is built one step at a time

Our relationship to investment is linked to our perception of time. The rise of the internet has completely this relationship with time. We live under the influence of mouse clicks. In an instant, they bring closer what was distant, unveil what was hidden, and offer us knowledge and consumer goods that once were foreign to us. This hyperconnectivity has profoundly changed our sense of time: the immediate has become the norm. Whether it’s buying a book, arranging a trip, getting information or placing a bet, we want it to happen quickly.

And yet life’s own cycle reminds us that life moves in stages, that every crop begins as a seed and takes time to grow. As brilliant as they may be, musicians and athletes need time to improve and in particular develop a certain consistency in the quality of their performance.

© Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Accumulation_function

The same goes for finance. Every long-lasting gain is built one step at a time. And each step is needed to enhance and consolidate everything that preceded it. Investing in a business, however successful it may be, calls for patience.

A new paradigm: speeding up the processes

The industrial revolution accelerated the pace of our lifestyles. The division of labour and automation of a large number of processes that previously had to be performed by individuals led to a continuous acceleration of the production and management of our resources. This was also the case with the management of financial asset. The increasingly invasive presence of the media had without doubt a role in this. The over-mediatisation of the stock market with stories of success resulted in many believing that randomly investing in the stock market is the easiest way to get high returns in the short term. It’s like saying we can buy a loaf of bread the day after sowing the wheat.

But artificial intelligence is only one of the weapons in what is known as the ‘passive asset management’ arsenal. This approach does away with analysing companies held in a portfolio. Instead it prefers to multiply tracker funds, the goal being to replicate the performance of the various stock market indices. There is little analysis, a bigger role for artificial intelligence and speculation. For fans of passive asset management, these are the ingredients that are expected to deliver extraordinary results in the short term.

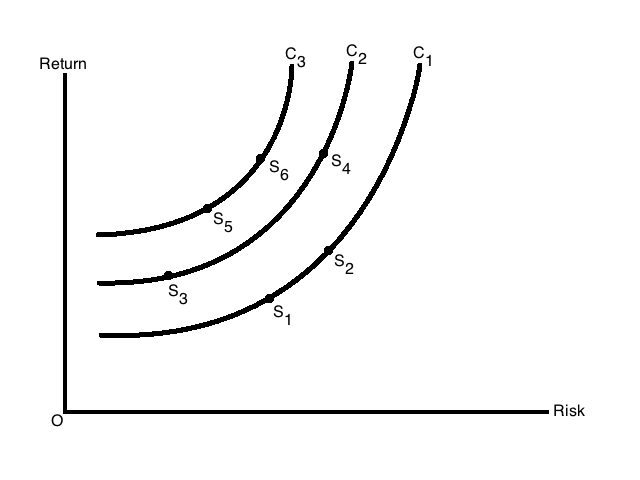

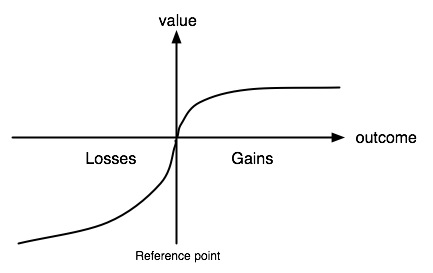

The varying perception of risk

The ground rules of investing according to Warren Buffett

Acknowledging the existence of risk and taking into account the human bias that causes certain probabilities to be over- or under-estimated based on the prospects they offer are the factors that investors must keep in mind. However, they are not the only ingredients for success, as the example of Warren Buffett demonstrates.

Two other principles are particularly important to Warren Buffett. Firstly, the need to buy shares in companies with high growth potential while they are still undervalued. And secondly, and this is his last guiding principle, you should only invest in businesses that you understand.

Simple principles for a complex world

Applying these principles on a daily basis

Bearing these different factors in mind, what is smart asset management? First and foremost it is a question of attitude. Investors who want both high returns and to avoid undue risk must understand that buying any given share means buying a long-term stake in the company. As Warren Buffett has done all his life, investing within a time frame that is compatible with the life of a company – in other words, long term – is one of the keys to success.

This is exactly the approach we take at Banque de Luxembourg, namely investing in high-quality companies that are well established in a stable sector (that we understand) and that promise a regular return. We analyse the market in depth and individually select companies that meet our objective criteria, without succumbing to market sirens. We think carefully about where we are going to invest, rather than pursue automated investments that are guided by the lure of a quick but unlikely profit. In short, we manage assets entrusted to us in the same way that our forebears managed their resources: over the long term, with care, and avoiding the risk of loss.